Sometime around when I was 14 or so I added a nickname to “Daddy” and “Daddy Bear,” the two standard names for my father, and began calling him Waltie Wonderful. In part, it was in response to his somewhat buttoned-up CEO persona that I liked to rib him about, because I knew the man behind that pin-striped suit, and he wasn’t all that serious, and also I was a smart-ass teenager, so.

But it was also because my dad was wonderful. He was funny and smart. He loved life. His enthusiasm lit up a room. His laugh brought delight. But his broad chest also encased a very tender heart. He could be easily hurt, although he’d never say so. There was a sweetness about him, as my mother said.

He’d been an English major at Brown University in the late 1930s, working three jobs to put himself through college, also with the aid of a few alumni patrons who saw his intelligence and charisma and figured he’d be a decent investment in the Brown lineage. They weren’t wrong. Everyone thought he was headed to law school, including him, but he ended up getting an MBA instead of a law degree and spent his long career in business.

One of his summer jobs to make money for college was working for a contractor in Akron, Ohio. There he discovered both the love and the knack for design. He built the house in Louisville, Kentucky that my parents brought me home to as a newborn, the youngest of three girls, and he remodeled pretty much every house we lived in, which was somewhere around fourteen or more.

He taught me to snap a chalk line and to apply mud to the nail holes in the drywall in so many of the remodeling projects he did, and then he taught me how to smooth out the mud and sand it when it dried. I helped him with a lot of projects, and by help I mean I held up the end of the long 2X4s while he nailed them in place and I secured the end of the scary metal measuring tape with the edges that could razor your fingers if it suddenly retracted. And I helped paint, and I used the nail punch to drive finishing nails into the quarter-round and dabbed wood putty into the holes. And I replenished his giant glass with ice and fresh tea and once in a while he’d let me use his SKIL saw on the simpler stuff.

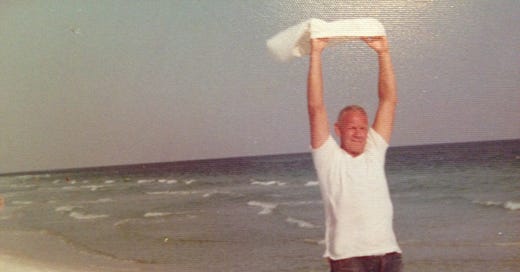

When we went on vacation every June to the as-yet-undiscovered Destin, Florida area, in the afternoons if it was too hot to be in the sun, Waltie Wonderful would instigate a poker game. Evenings he’d put on clean blue jean cut-offs and a clean white t-shirt and take my mom and my sisters and me out to a hole-in-the-wall seafood place, where there’d be cold beer and homemade blue cheese dressing for the crisp iceberg lettuce and hot hush puppies and fried shrimp and battered hunks of fresh-caught mackerel.

Some mornings he and I would race on the empty beach, and for a long time I was no match for the long legs on his 6’3” frame, but when I was twenty-two I beat him, and it quieted us both for a good long minute, this reversal of generations — him slowing down and me finding my stride.

We were close. He understood me in a way my mom didn’t. For my 18th birthday he gave me framed verses from Wordsworth’s “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood.”

Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting:

The Soul that rises with us, our life's Star,

Hath had elsewhere its setting,

And cometh from afar:

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter nakedness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home:

Heaven lies about us in our infancy!

He was not a religious man, but after I was ordained, he teared up every time I gave him communion. Tiptoeing around any mention of God, he often spoke of “the Man Upstairs,” even after one of my sisters died of breast cancer, a loss that broke him for years in ways that he never fully came back from. And how could he?

He avidly read my first two novels and offered amazing edits. If he hadn’t developed dementia, maybe he would have been my editor. Maybe we would have written a book together. He had plenty of stories to tell. Instead, he gradually disappeared from us, as if he was on a slow-moving raft crossing still, deep waters, almost imperceptibly drifting out of reach until it we nearly became strangers to each other.

He died May 11, 2009, after aspirating his daily dose of heart and blood pressure pills, not even a month after his 93rd birthday, which was April 24th. I miss him every day.

Hug your dads if you’ve got ‘em. Mine could be a jerk, I’m not gonna lie. Don’t we all have our ugly moments? He could be arrogant and stubborn, and he and my mom each gave as good as they got, sometimes aiming cruel potshots at each other. He was such a dreadful tipper that one of us always lingered after — “Oh, I left my ______ (lip gloss, favorite pen, glasses, etc.)” — to fish around in our purse for another couple of dollar bills to leave on the restaurant table.

But mostly he was kind and loyal and wanted the best for people. He came from meager circumstances and never forgot it. The day in 1968 when he came home with a brand new RCA color television, we were all stunned.

“You what?” my ultra-thrifty mother exclaimed.

We watched a lot of football games on that TV, my dad with the stub of a Dutch Masters cigar clenched in his teeth, shaking his fist and shouting “Goddammit!” at the deeply-detested Green Bay Packers while a slight smile tugged at the corners of my mother’s mouth.

Wherever you are Waltie Wonderful, I hope the beer is cold, the cigars are excellent, and the Packers are perpetually getting their asses kicked. I hope there’s music and dancing — remember how you taught me to waltz, 1, 2, 3 - 1, 2, 3? — and that you and mom are walking along some perfect, pristine beach where the turquoise water laps at your feet and the setting sun, hanging like a well-kept promise, never disappears but bathes you both in that eternal golden light.

Even though I told you the night you were dying, I’m not sure you heard me, so I’ll say it again. Thanks for being my dad. Really. You were truly wonderful.

So beautiful

Very bittersweet memory. I really liked Walt and believe the sentiment was reciprocated. I remember how proud he was of the new ceiling in the Tulane Road house and how he looked up at it every time he visited. It was so enjoyable working on that project with him, trying to retain all the framing and drywall knowledge he was imparting. It's easy to understand why and how you miss him.